11th August 2024

The True Value of Method of Movement

It appears to me that when people talk about Leigh Howard Stevens' Method of Movement, it's mainly about the 590 exercises. Sure, that's a lot of exercises, and the book is comprehensive in its detail, but I would argue that its true value lies elsewhere.

Before the music starts (and after, in my 1993 copy), there is a wealth of information regarding the marimba, percussion, and life in general. People tend to skip over this, and Stevens was aware of this. I know this because of what he wrote in the revised version:

"Read the book. Carefully. From the beginning." (page 100)

Obviously, people didn't. And it's their loss, because the exercises themselves can be largely worked out logically. I think that Stevens could have written a quarter of the exercises and any smart percussionist could have worked out the rest. However, they couldn't have done without the text at the beginning, and to a lesser extent, the text at the end. Below are some quotes that have resonated with me over the years:

"It is safe to say that chords voiced with equal dynamics and timbre are a rarity in expressive performance." (page 23)

Why be boring? I bring this up with my piano students all of the time, in regards to dynamics. Just because a chord is marked at a certain dynamic doesn't mean that all of the notes should sound at the exact same volume. Sure, that may be the case some of the time, but as Stevens says, it's a rarity (or at least, it should be).

"...you should be trying to develop...the meticulous, efficient and logical habits of movement which you want to have permanently. There is no other reason to practice [sic] technical exercises on a musical instrument....if you are not consciously thinking about and trying to control how the stroke or shift is supposed to be performed, you will end up developing...the illogical habits of movement you probably had before. This is worse than a waste of time; it is counterproductive." (page 100)

This is a big quote, so I've chopped it down. Technical exercises are not designed to be musically interesting. Because of this, I often have to repeatedly tell myself to concentrate while practising technique. If you're "off with the fairies" you will likely not be making good use of your time. You may even be technically regressing. In short, concentrate!

"If one craves long mellow struck tones, use a large, soft mallet to cancel the overtones, and strike the bar with great velocity. If this won't do, switch to cello..." (page 22)

No instrument or technique can do everything. The piano can do a lot, but just try to achieve a crescendo on a long-held note. Can't do it, can you? It's important to remember that all instruments and techniques are a compromise. For one of my areas of expertise, six-mallet percussion, it's a given that alternating D-flat and D major root position chords are near impossible using a single hand. Add in speed, and stipulate that the bars must be struck in the centre, and you've got yourself a physical impossibility. Does this invalidate the entire six-mallet technique? Of course not. One should weigh up the pros and cons of any technique when considering study. Do I want to play a heap of root position chords? Personally, no. I'm currently writing about this in an article about six-mallet percussion, so I'll leave further discussion on this topic for another time. The takeaway from the quote is that you won't get everything from a single instrument or technique. And that's ok.

"If the above mentioned factors...have been ignored...the imagination will have no musical reflexes to call on. Such a player is left with perhaps a good general technique but a frustrating inability to produce the sounds he hears in his mind. Sadder still is the player who strives to control elements of tone only to find out years later that there is no substantial musical imagination to trigger those hard-earned reflexes." (page 23)

Musical imagination always trumps technique. It's as simple as that. Imagination creates new things, new ideas. Technique is simply an application of those ideas, and if you don't have any, then your technique is pointless.

I think that the Stevens book should be required reading for all percussion students. It doesn't matter if you're using his technique or not; it doesn't even matter if you don't play four mallets. The ideas in the text alone are worth the price of purchase.

3rd August 2024

Relative Pitch Notation In Lilypond

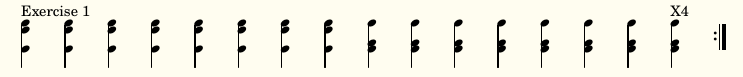

I'm in the process of writing some six mallet exercises. As I mentioned last month (click here for details), I prefer to do a lot of my technical work away from any instrument. For this reason, I like to write my exercises with relative, rather than absolute pitches. This way, the reader can see the relative distances between mallets. For example, they could be evenly spaced, or with two mallets close together.

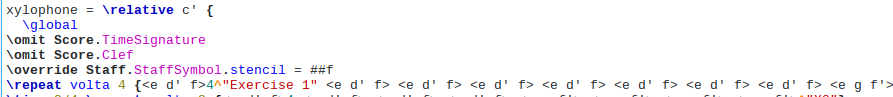

This is incredibly easy to achieve in Lilypond. Simply enter the notes with pitches, as you would normally, and then remove the staff. I like to work in the treble staff, so my evenly spaced notes are on the E, B, and F lines. Using E, G, and F lines indicates that the lower mallets are closer together, and E, D, and F lines are used for close upper mallets. The staff can be removed using the following command:

\override Staff.StaffSymbol.stencil = ##f

As there is no staff, there is no point in having a clef, so this can be removed by typing:

\omit Score.Clef

And that's all there is to it. Below is a snippet of the code (with a few additions), followed by the resulting sheet music.

For previous months, click here.