31st May 2024

(Some) Music = Melody + Chords + Pyrotechnics

I’ve been playing through a lot of Chopin and Liszt’s virtuoso piano repertoire recently, and I absolutely love it. In fact, I play a lot of it at half speed, not because that is the limit of my technique (although 50% is pushing it for me), but because it’s interesting hearing how the notes come together at a speed that my brain can process it.

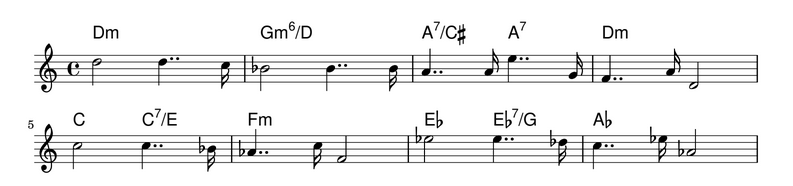

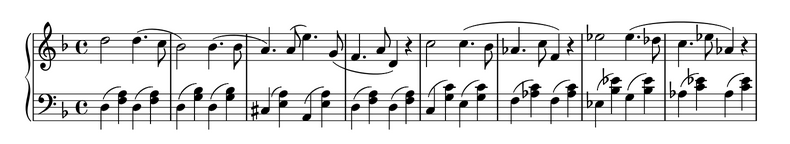

At this speed it became apparent to me that a lot of virtuoso piano music of the early 19th century follows a fairly simple formula: music = melody + chords + pyrotechnics. There’s nothing wrong with it, whether it’s fairly blatant (Chopin Op. 10 No. 1), or slightly more hidden (Transcendental Etude No. 4). What this does allow is the substitution of the pyrotechnics for something else. For example, it’s easy to disect Transcendental Etude No. 4 (first image) into melody and chords (second image), and then into something resembling an oompah band (third image). Keep the melody, cut out the pyrotechnics, and change the bass and chords into something resembling Mozart’s Rondo Alla Turca. Simple.

I’m not advocating the perfomance of this by your local German band by any means (although I’d definitely come and watch it). What I am suggesting is that by analysis of how a piece is constructed, variations, adaptations, and general butchering of a piece can be easily achieved.

One example that stretches as far from butchering as humanly possible is Godowsky’s variations on Chopin’s Op. 10 and Op. 25 etudes. Godowski was a genius, but there was a reason that he specifically chose Chopin’s etudes; that is, that their design invites alteration in all kinds of different ways.

For previous months, click here.