9th March 2024

Introducing Lilypond

Music notators, have you considered Lilypond? It’s powerful, it’s free, the output looks amazing, but it is also quite complicated, especially for beginners. In this post, I will explain what Lilypond is, how to use it, and when I think the time spent to learn it is justified.

Firstly, let’s briefly cover what Lilypond is, and more importantly, what it is not. Lilypond is available for Windows, MacOS, and Linux. It is a program that converts written instructions into musical notation. It is not a notation program like Finale, where notes can be placed on the staff using the mouse. This means that (a large amount of) syntax has to be learned in order to create complicated scores.

It can be done, however. My doctoral dissertation included an adaptation of John Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes for multiple percussion (all twenty sections). It included cross-staff beaming (there were five simultaneous percussion staves), three levels of nested triplets, dead strokes, mallet numberings (some movements were for six-mallets), and much more. Almost all of the time, Lilypond put the notes, annotations, and various other markings exactly where I would have chosen, and the few times that I didn’t like the output, tweaking it was relatively pain-free. In fact, out of all of the components that made up my doctorate, notation was probably the easiest.

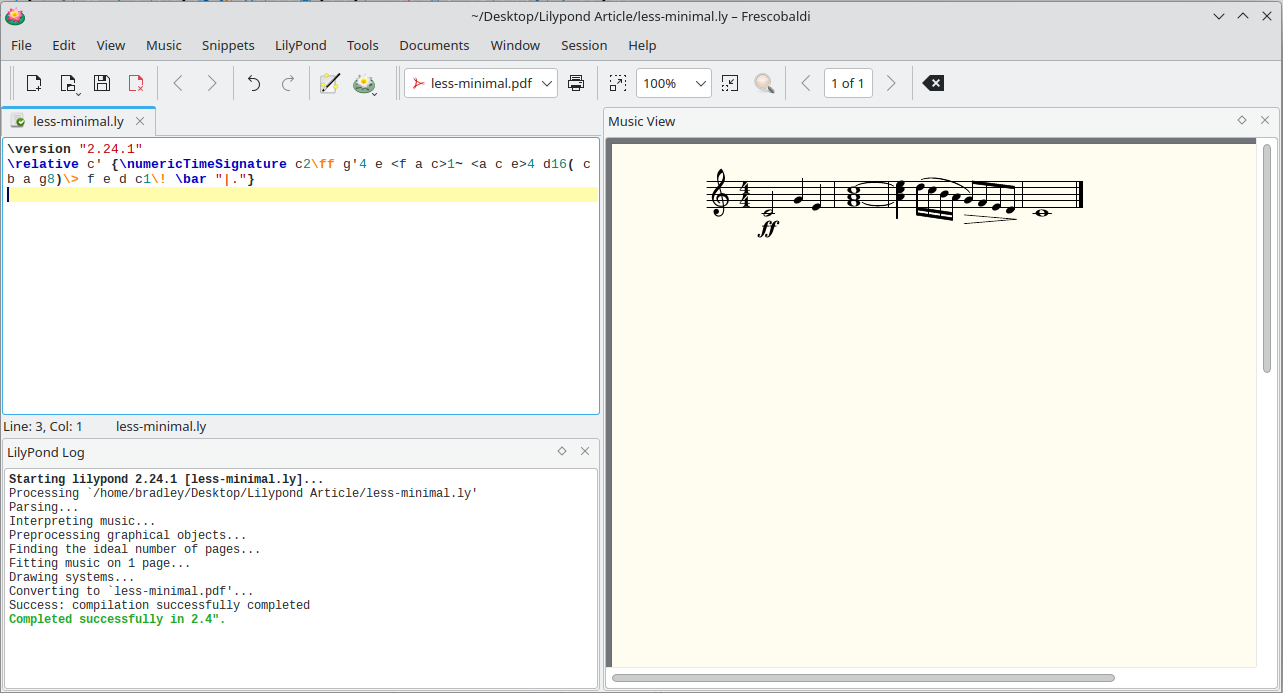

Lilypond input files are just text documents, saved with the extension “.ly”. Opening the file in Lilypond sends the text directions to the program, which shoots out a PDF. Usually. If you don’t end up with one, then you may have to troubleshoot your file. This is quite a complicated affair, and for that reason I recommend using a graphical front end to Lilypond called Frescobaldi. This program is also available for Windows, MacOS, and Linux, and can produce Lilypond output on-the-fly. As soon as it sees that the input file has changed to a certain degree, it re-compiles the instructions into a PDF, and then previews that PDF within the window. In the following picture, you can see the text instructions on the left, with the log (list of operations and errors) underneath. On the right is the musical output.

Of course no single article will be able to describe all that Lilypond can do. However, here are a few ideas:

- Lilypond will (using the relative setting, as in line 2) pick the closest pitch of that particular class. Change the octave by using ‘ for up an octave, and , for down an octave.

- Change note values using numbers. 1 = whole note, 2 = half note, 4 = quarter note etc. Lilypond will assume that you want to keep the same note value unless told otherwise.

- Use \numericTimeSignature to get rid of the C in the time signature.

- Make chords by enclosing notes with < > (the pitch of the first note in the chord is used to pitch subsequent notes).

- Tie notes by using ~ after the first one.

- Slurs start with ( after the note and end with ) after the note.

- Dynamics use a \ followed by the marking. Use \< for crescendo, \> for diminuendo. Hairpins are terminated by a dynamic marking or \!

- Various barlines can be inserted by using the \bar command. \bar “|.” gives a double barline.

The following “less-minimal” example shows all of these:

You may have noticed that the log includes the compilation time. For simple scores this is almost simultaneous, for some of my most complicated Sonatas and Interludes scores it took a couple of minutes to compile. These were, however, very complicated scores, and I was compiling them on a 2010-era netbook. On the topic of compilation speed, my very rudimentary research (using htop) indicates that Lilypond (and Frescobaldi) appear to only use a single processor thread, so your 64-core server isn’t going to compile things any faster.

So, who is Lilypond for? If you only create scores a few times a year, the learning time isn’t going to be worth it. If, however, you spend time in front of a score editor almost every day, you have a computer that isn’t more than ten years old, and you want your scores to look absolutely amazing, give it a try. After all, it’s free. Get Lilypond (and Frescobaldi), then go to https://lilypond.org/doc/v2.24/Documentation/notation/index.html and learn even more.

If reading a documentation website isn’t your style, keep following this blog; I’ll be uploading miniature Lilypond lessons every so often.

For previous months, click here.